Employers around the world need to recommit themselves to doing more to make it easier for women to work and lead.

Women across the world are still battling a “double whammy” of social expectations that are at odds with the expectations they face in the workplace, and this conflict is effectively keeping them from climbing the corporate ladder.

According to a newly released survey from the Global Network for Advanced Management, women across the world are caught between a rock and a hard place. Their communities reward congenial, non-competitive personalities and playing a large role in the family, while the workplace expects long hours and assertiveness. To make matters more complicated, many women feel—paradoxically—that their employers would dislike them if they do not appear family-oriented, despite the fact that they feel long hours are expected of them. This push-pull factor of conflicting expectations is a global phenomenon.

There is overwhelming evidence that diversifying the talent pool is good for business. This applies to race, gender and many other factors. For starters, it means that one increases the size of the available talent pool and potentially represents a more diverse customer base. And yet women are still facing difficulties in the workplace and disproportionate representation in leadership roles. Although they make up more than half of the workforce, they are still in the minority of leadership roles. In fact, 39% of companies in G7 countries have no women in senior roles at all.

The Global Network survey was designed by political scientists Frances Rosenbluth, Gareth Nellis, and Michael Weaver; the 4,881 students and alumni who responded represent 28 business schools worldwide, including the UCT Graduate School of Business in South Africa. The study’s authors noted the respondents’ expectation that women will play a more active role in childcare; logically, it should follow that they will spend less time at work, be less productive, and be less career-oriented. But to get ahead professionally, the opposite is expected of them.

“Female employees are likely to be on the horns of a dilemma: spending hours at work might help them get promoted, but their boss (and everyone else) may at the same time dislike them for bucking societal expectations,” the authors write. “Male employees who choose to invest time in their careers may face less disapproval for reducing time devoted to childcare. Around the world the presumption is that the mother should bear more than 50% of the responsibility for childcare.”

These findings should shock us, but perhaps the most important outcome of the survey is the most obvious: combatting gender inequality in the workplace is not somebody else’s problem. The study emphasizes the signals sent by employers “whether or not they intend to send [them],” which underlines the need for explicitly communicated support for women from the top. It is up to employers, the report notes, to convince women that they do not have to straddle a complex web of expectations in the workplace.

The Global Network recommendations are simple, yet potentially very effective. Given that women are often caught between a disproportionately large family role and rewards for what the authors call “pleasing personalities,” whereas workplaces reward long hours on the job and assertiveness, employers can make supportive decisions armed with this knowledge. “[They] can take measures that make for stronger, more attractive workplace environments,” the authors write.

Key suggestions include:

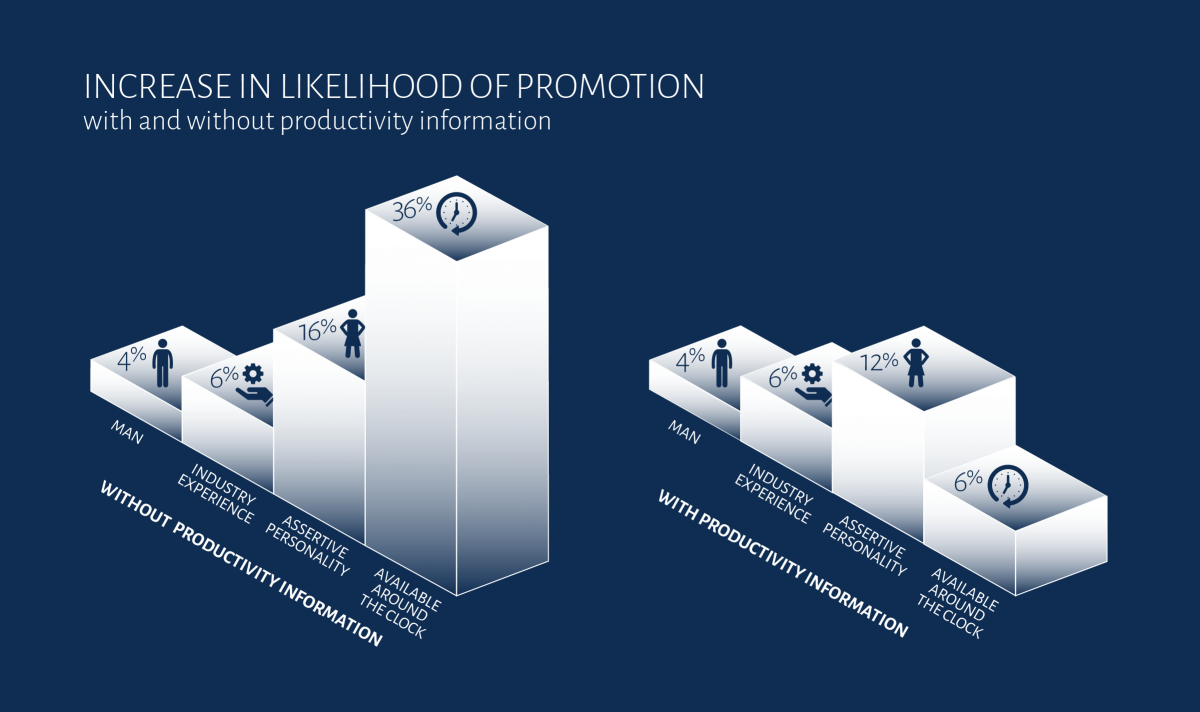

1) Reward productivity, not hours worked in the office. Data presented to the survey respondents revealed that around-the-clock availability did not increase an employee’s productivity. When this was made clear to respondents, their preference for employees with a high level of after-hours availability fell away.

2) Support personality differences, acknowledging the value of diversity, and reward non-assertive but effective approaches. Diversity builds a stronger workforce.

3) Encourage fathers who may want to be more involved in childcare than is assumed, in order to counter the perception that childcare is primarily a woman’s responsibility. This is also more supportive to fathers who do want to spend more time with their children, but find that workplaces are not conducive to hands-on fathering.

4) Use the ability to work remotely to allow for workplace flexibility rather than as a limitless extension of the office. The study found that working remotely was viewed in a positive light when it was done after hours, but in a negative light when it was done during office hours. This effectively means that working remotely does not necessarily increase flexibility, but rather that there is a stigma attached to those who must take advantage of it. Consider the positive and negative effects of the ability to work remotely on employees, suggest the authors. Companies that develop a culture that supports women in the workplace also encourage a healthy work-life balance for all employees. Such a culture could prove an advantage in the competition for the best talent.

Employers cannot take on a patriarchal society at large, but they can provide a supportive environment to women trying to navigate the complex path between conflicting expectations. Those in senior roles though they may not realise it, have the power to exacerbate or relieve the pressure employees are feeling to conform to perceived expectations.

Building more flexible and more accepting organizations that explicitly express support for women will not only benefit women, but also men. And the business as a whole will benefit from a more diverse and committed workforce. Now that’s something worth standing up for.

The findings of the Global Network for Advanced Management’s survey “Women in the Global Workforce” were presented via a webinar on March 8, moderated by Della Bradshaw, former business education editor of the Financial Times. It was hosted by the Saïd Business School and featured a discussion panel of Global Network faculty, including Kellie McElhaney (Faculty Director, Center for Gender Leadership, Haas School of Business), Frances McCall Rosenbluth (Damon Wells Professor of Political Science, Yale University), and Kathy Harvey (Associate Dean for the MBA and Executive Degrees, Saïd Business School); their remarks are excerpted here.