Managing IS/IT successfully is becoming increasingly difficult in today's dynamic business and technology environments. The challenge is to harness digital technologies both in achieving alignment with current enterprise objectives and innovating to create new strategies and business capabilities.

Many companies are on a mad rush to embrace the so called internet of things (IoT). It seems that everyone is doing so and that it would be a strategic mistake not to do so. And, if we are to believe all the hype, the payback is enormous.

Many companies are on a mad rush to embrace the so called internet of things (IoT). It seems that everyone is doing so and that it would be a strategic mistake not to do so. And, if we are to believe all the hype, the payback is enormous.

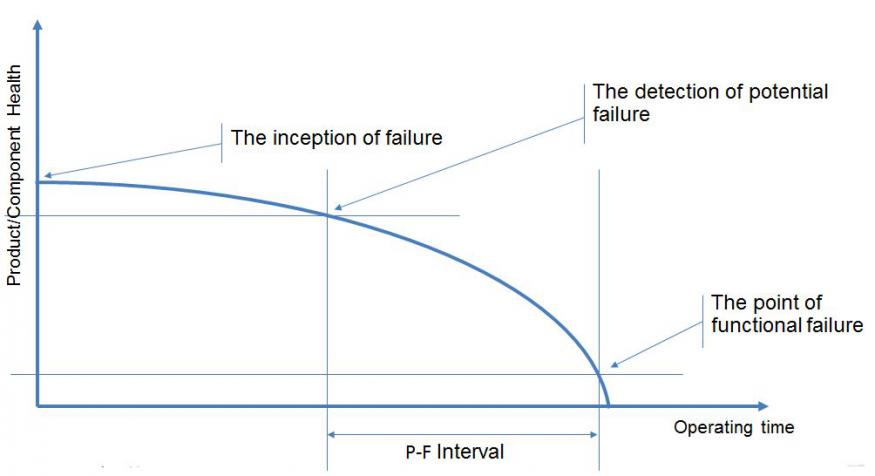

While the latter can be true, it is important to first understand what is and isn’t possible. For example, one argument being made for “instrumenting” machines in factories — installing sensors and connecting them together — is to improve their up-time and thus the overall efficiency of production. The assumption is that potential problems with these machines can be detected, point of failure predicted and that there is a time interval to rectify any problem identified. This may not be the case. Figure 1 maps the ‘health’ of a product, asset or component against its operating time, illustrating what is known as the P-F (potential-to-functional failure) interval. The P-F interval is the time between detecting something will fail and actual failure. This time interval must be long enough so that any problem can be rectified without impacting operational performance. The challenge becomes a bit more complicated if a product or asset has multiple points of failure with different P-F intervals.

Attaching sensors to collect data from a product when in use by a customer also provides many opportunities. For example, it might enable an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) to rethink its business model, shifting from perhaps one based on selling a product with ownership passing to the customer to one centered on the availability of the product, with the customer purchasing the service rendered by the product. This is what Rolls-Royce does with their “Power-by-the-Hour” proposition; airlines contract for availability of the engine and are essentially buying thrust. However, to make this proposition commercially viable, the OEM will usually need to collect data that will detect the onset of problems before they actually impact performance and result in product failure. Non-availability of the product usually incurs significant penalties.

When GE sell a wind turbine or a whole farm of wind turbines, they have a software offering — PowerUp — which takes data from turbine-based sensors, combines it with their domain knowledge in aerodynamics and changes the curvature of blades to adapt each wind turbine to the wind that’s hitting it. That enables operators to generate up to 5% more electricity and 20% more profit per turbine.

Data might also be collected not to directly improve the performance of a product, asset or structure but used for another purpose. For example, collecting telemetry data on engine performance can indicate how well a person is driving a car. For an insurance company, this information is very valuable. Historically, actuaries have used data such as age, gender, number of years driving, previous claims history and one or two other data points to assess the risk of someone having an accident and making a claim. Today, they can collect data on actual driver behavior and assess how good a person is at driving. This enables them to calculate risk based on actual driver behavior and not based on surrogate measures.

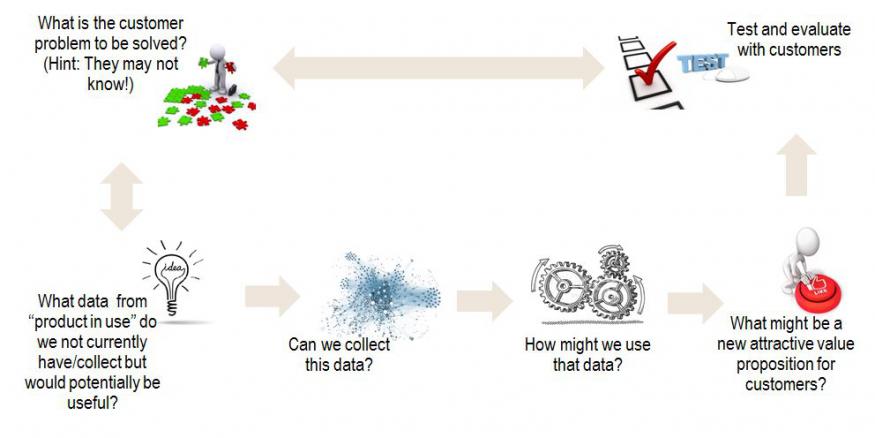

IoT is actually a bit of a misnomer; it really means that data from a variety of sources (devices, locations, etc.) can potentially be made available for direct use or combined with other data. The challenge is to figure out how to use all this data. Sometime the use is well established. At other times it will demand creativity. It often helps to explore whether the problem can be framed in terms of a data problem. Figure 2 presents the outline of an approach that can help guide this process of exploring data to identify opportunities.

As a starting point, we could begin with understand the customer pain points. Where are their problems, issues and challenges? Mapping the customer journey can be useful in identifying these. Talking to customers can also be revealing. However, sometimes customers themselves struggle to see their problems or to express them in different ways and there are techniques to help in uncovering these “hidden” needs. Once identified, the challenge is to figure out how we might address these with the additional data. A methodology like design thinking — a human-centered, prototype-driven process for innovation — can be very powerful in building a more empathetic picture of the customer, taking abstract ideas and creating something with more tangible them.

It can also be helpful to frame the customer problem as an information problem. Take something seemingly as mundane as parking, for example. In a city like Los Angeles, it is estimated that 30% of the traffic is actually drivers looking for a space to park their car. Expressed in data terms, drivers lack information about where empty spaces are, while empty spaces don’t know which drivers are searching for a place to park. Sensors in parking spaces can detect whether they are vacant and today there are mobile apps that make this information available to drivers. Uber works on the same principle, framing the problem not about making a taxi company more efficient in how it operates its call center and dispatch but as a data problem concerned with customer not knowing which drivers are looking for fares and where they are.

An alternative starting point is to consider data that could potentially be collected from physical things and what opportunities having this data might open up. This usually demands some creative thinking. It might lead to the articulation of a new value proposition for customers. This proposition would then need to be tested with customers, with feedback either refining the original idea or rejection. This is an iterative process based on experimentation and learning.

There is no blueprint for IoT or roadmap that with take you on the Industry 4.0 journey. It takes time and effort and will invariably demand challenging dominant views of customers, product and industries. Seeing what others have done, perhaps in other domains, can be useful in sparking ideas. While the concept of the IoT might be new, figuring out how to leverage data has been a quest for many decades and one which most companies have struggled with and continue to do.