Yale School of Management United States

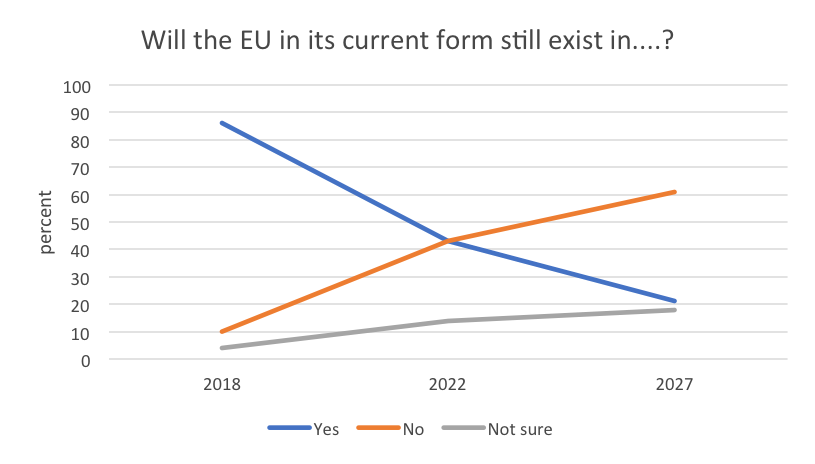

The third session of our experimental “The End of Globalization?” online course for students from across the Global Network for Advanced Management revealed just how uncertain MBAs think Europe’s future is. At the end of a 90-minute discussion about the causes and consequences of Brexit, we asked students whether they thought the EU (minus the UK, but otherwise in its current form) will still exist one, five, and 10 years from now.

Despite the string of elections this year that could propel anti-EU populists to power, including Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, Marine Le Pen in France, and Beppe Grillo in Italy, and that could end Angela Merkel’s long reign in Germany, 86% of students are confident the EU will be around next year. When it comes to 2022, however, just as many believe the EU will have changed dramatically or have disappeared as believe it will still exist in its current form. And almost two in three students are convinced the current EU will be a thing of the past by 2027.

Indeed, as the session revealed, the EU is dealing with a myriad of crises, from renewed concern over Greece, to still-weak banks in Italy and beyond, to a refugee and immigration crisis and an employment crisis that afflicts particularly the young. Add to this the crisis posed by Brexit and European leaders have their hands full. The biggest crisis of all, however, and one made more pronounced by Brexit, is a crisis of legitimacy, as David R. Cameron, professor of political science and director of European Union studies at Yale University, explained to the Global Network students.

Cameron was the featured guest in the session and shared with students his views on why his namesake, the former British Prime Minister David Cameron, miscalculated so badly when he called for a referendum on Britain’s continued membership in the EU. Not only was the question asked too narrowly (“remain” or “leave,” with no consideration of what a world without the EU might look like), he argued, but Cameron and his allies also ran a dreadful campaign that framed the issue almost exclusively in terms of the negative impact of leaving the EU on the economy, jobs, and investments—an approach that became known as “Project Fear.” Brexit proponents, in contrast, captured the imagination especially of older voters, less educated voters, and those in the former industrial heartland with their cry for Britons to “take their country back.”

“I was up all night watching the results of the referendum come in,” explained Cameron,“but when I saw that Sunderland had overwhelmingly voted to leave, I knew it was over. If a solidly Labour district with a large Nissan plant that manufactures cars largely for the European market votes to quit, it’s clear that economic rationale was not going to prevail.”

For many British voters, immigration was the key issue, and those who were particularly concerned about a recent increase in immigration from fellow EU countries mired in economic crisis voted overwhelmingly to quit the EU. “Since its founding, the European Economic Community and later the European Union has had this focus on the ‘four freedoms’—the creation of an internal market in which goods, services, capital, and people could move freely,” explained Cameron. While the British economy has benefited from European integration, older and poorer voters in particular felt that the free flow of people from other EU countries had hurt them. Yet European leaders were unwilling to let Britain pick and choose, and for this position they got the support of Global Network students. Polled on whether they think European leaders should have allowed the UK to suspend or limit EU migration in an effort to appease British voters, 65 percent said “definitely not” or “probably not.” And it is this insistence of the EU that the four freedoms go together that has left current Prime Minister Theresa May no choice but to opt for “hard” Brexit, Cameron concluded.

Having examined in a previous session of the course the rise of populists from the U.S. to Asia and Europe, enrolled students believe that the wave that saw Donald Trump elected in the U.S. and Rodrigo Duterte take power in the Philippines, and that has emboldened populist leaders in Hungary, Poland, Turkey, and other countries, is not over. A plurality of 44% of students enrolled in the course think that Marine Le Pen, leader of the populist anti-EU and anti-immigrant Front National, will become the next president of France after elections in April and May. A similar plurality think Geert Wilders of the anti-establishment Dutch Freedom Party will win his country’s parliamentary election in March. Things are less certain in Italy. While 37% of students think that Beppe Grillo, leader of the populist Five Star Movement, could become Italian prime minister if there are early elections this year, 47% are not sure. Students have the most confidence in the outcome of Germany’s elections in the fall. Even though the populist Alternative für Deutschland has been gaining in the polls and the Social Democratic Party, Chancellor Merkel’s junior coalition partner, has nominated with former European Parliament president Martin Schulz a popular alternative, 55% of students are convinced Angela Merkel will be reelected as chancellor.

In his closing comments, Cameron stressed his optimism regarding the future of the European project despite the colossal challenges. “Europe always does best when in crisis,” Cameron explained, and now that the perennially EU-ambivalent UK has withdrawn, there is an opportunity for the remaining members to forge ahead with “ever closer union.” Cameron revealed that on the question of whether the EU will still be around in one, five, and 10 years, he would have voted “yes,” “yes,” and “yes.”